This article contains references to sexual assault and suicide.

Doing an army crawl while covered in molasses, raw eggs and woodchips. Going on a nude run. Climbing up the roof of a silo.

These are some of the rituals students say they go through to join a secret society at Western Sydney University.

Known as HAC, the student-run collective is based at the university’s Hawkesbury campus north-west of Sydney.

The name harks back to Hawkesbury Agricultural College: the original college that occupied the campus, before it merged with Western Sydney University in 1989.

Patrick (not his real name) is a member of HAC, which still does some of the activities and traditions that date back more than 130 years.

“Obviously, we do have parties, we do get drunk … there is a power dynamic, but I think it’s a lot more teaching-based,” he said.

One of HAC’s traditions is a drinking game where first-years are quizzed on the history of the campus, and must drink if they answer incorrectly. Source: SBS

HAC is comparable to a fraternity you’d see at an American college, Patrick said.

As a third-year student, he’s at the top of the hierarchy: his job is to initiate the first-years into the group, which is called motting.

“The third-years have this sort of power over the first-years,” he explained.

Part of the initiation is a trivia-based drinking game, where you’ll be quizzed on the history of the campus. Answer incorrectly and you’ll be made to take a swig of booze.

Patrick looks back fondly on his own time as a first-year.

“I’m a young male, I’m going to have some drinks, and this was just a good excuse,” he said.

Once you pass the initiation, Patrick says you’re given a nickname and are officially part of HAC.

In recent years, the group’s pranks and events have included mock marriage proposals, putting on talent shows and filling other members’ dorm rooms with sawdust or balloons.

Mock marriage proposals are part of HAC’s traditions, where students ‘propose’ to each other and the best couple is married in a fake ceremony. Source: Supplied

Then Patrick says there are the “battles” between the boys and girls. With the boys dressed in button-up shirts and the girls in skirts, they each try to capture as many shirts and skirts as possible from the opposite gender.

“It can tend to get a little bit violent really, but everyone loves it,” Patrick told The Feed.

“One of the people a year above me broke his finger at one of them, but he doesn’t regret it … he brings it up as a fun story for sure.”

Patrick says in recent years, the group has gone further underground because of the university’s hazing and motting ban.

“Anyone who is associated with the group on the first occasion, they immediately have a six-month suspension, and on the second occasion, they have an immediate expulsion from the university,” Patrick said.

Patrick says he was almost suspended in his first year for taking part in the group’s rituals during his initiation.

He also says he was evicted from his on-campus accommodation.

Past pranks have included members filling each other’s dorm rooms with sawdust or balloons. Source: Supplied

“That was honestly one of the hardest periods of my life, because the amount of housing insecurity that caused,” he said.

“I think the university’s cracked down on it in the wrong kind of way.”

The Feed asked Western Sydney University about HAC and its activities.

A spokesperson said while HAC is not technically banned as it’s not a registered club, the university takes a strong stance against motting.

“Students associated with HAC have previously engaged in motting and hazing activities, with students subjected to a number of often dangerous or publicly-humiliating activities in which they are forced to take part or incur penalties,” the spokesperson told The Feed.

“We have a clear policy in relation to motting and hazing and misconduct — taking a zero-tolerance approach to any behaviour that endangers students by placing them in coercive, sexualised contexts and activities during which drugs or alcohol are consumed.”

Hazing nicknames are now banned on campus, but the nicknames of students from past decades are scrawled under the university’s rugby union scoreboard. Source: Supplied

The university has also banned HAC nicknames, believing they “often have underlying sexualised or derogatory associations”.

Patrick said while the nicknames are often sexual puns, these days they’re randomly taken from a list and aren’t based on a student’s personal characteristics.

What is hazing ?

Hazing is a form of initiation required to enter a group — some of those who do it say it encourages bonding but others say the activities can sometimes be humiliating or degrading.

Aashish Srivastava, a senior lecturer at Monash University, has researched the culture of hazing. He says in Australia, it mostly occurs within university residential colleges and the defence force.

“Hazing is a dominance of power … the senior members of a group, they actually want to show their superiority and dominance over junior members or new members who join the group,” he said.

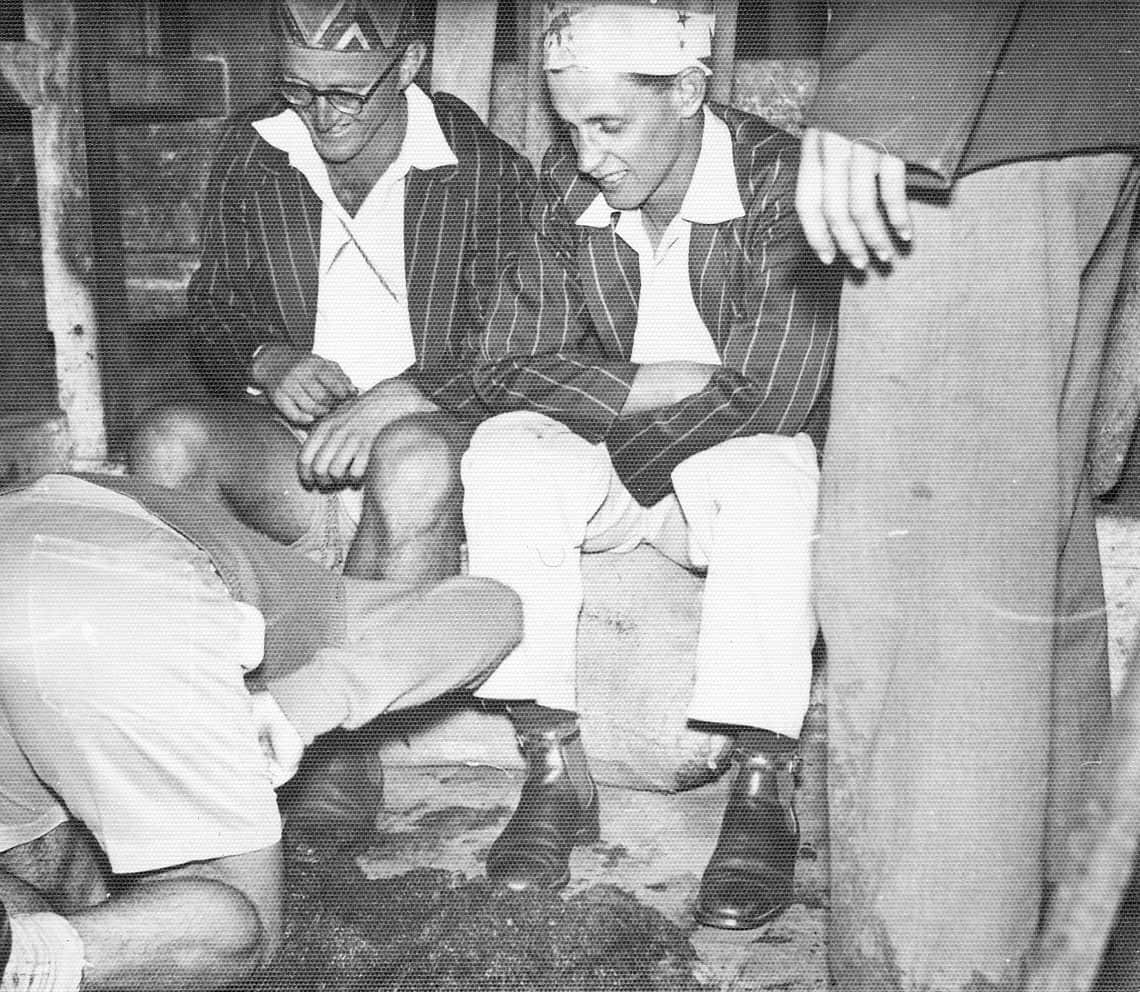

A group of first-year students taking part in motting in 1955. Credit: Western Sydney University Archives Collection: Ref. D16/1470597

The not-so-secret society

HAC’s motting rituals weren’t always done in secret — they used to be performed openly when the campus was an agricultural college.

“It was definitely an established culture. The campus used to run activities on O-week (orientation week) that a lot of our traditions are based on,” Patrick said.

Founded in 1891, the campus was a wilder place in previous decades. In Western Sydney University’s public archive, you can still find photos of the group’s rituals.

One tradition involved dropping off students up to 200km away to find their own way back to campus. When it was an all-boys college (it accepted its first female students in 1971), they would sometimes be stripped of their clothes.

Students, like this group from 1962, were taken kilometres away from the campus and had to make their own way back. Credit: Western Sydney University Archives Collection: Ref. D19/413627

During orientation week, senior students were also assigned roles such as King, Queen and Sergeant Major, and first-years had to obey their orders.

A study of student behaviour on campus from 1979, found in the university archives, described the role of Sergeant Major:

“He dragged around on a string his ‘pet’, a piglet dead for three days. Some initiates were later to be ordered to kiss or drag around this dead pig,” the authors wrote.

Initiates had to obey orders from the older students nominated “King” and “Queen”. Source: Supplied / Western Sydney University Archives Collection: Ref. D16/1470765

Past initiates also rowed in mud and kitchen slops, acted like sheep and were “auctioned” off to the highest bidder.

Some former students argued the initiations broke down class divides and improved bonding.

“It brought everyone down to the same level, and when it was all over, the hand of friendship and comradeship was always extended to all freshers by all the older students,” one former student told the Hawkesbury Agricultural Journal in 1971.

Mots “rowing” in a mixture of mud and kitchen slops in 1962. Credit: Western Sydney University Archives Collection: Ref. D19/413627

The culture on campuses has shifted since then — with most Australian universities now having anti-hazing policies.

Western Sydney University’s spokesperson said: “We make no apologies for taking a very strong and principled stand on what is acceptable behaviour, both on campus and within our student residences.”

“Anti-social behaviour and on-campus rituals have no place in today’s modern Australian university.”

The dark history of hazing at universities

While some hazing rituals are seen as harmless fun by some students, for others they can be damaging and dangerous.

In 2017, the Australian Human Rights Commission released a report on sexual violence at Australian universities. It found many hazing practices at universities involved elements of sexual assault and harassment.

“Hazing practices and college ‘traditions’ facilitate a culture which may increase the likelihood of sexual violence,” the report said.

Disturbing hazing practices were also uncovered inside Australia’s university residential colleges in a report by End Rape on Campus Australia in 2018.

At the University of Sydney, some hazing rituals involved male students masturbating into female students’ shampoo bottles and red-headed residents setting their pubic hair on fire to gain leadership positions.

Aashish Srivastava says initiation rituals at universities have often involved students consuming excessive amounts of alcohol.

Aashish Srivastava is s senior lecturer at Monash University who has studied hazing rituals in Australia and overseas. Source: Supplied

“Especially fresher girls or women … they have been coerced into drinking alcohol. And often it has also led to sexual harassment and sexual assault by other male members or senior members of the group,” he said.

At Western Sydney University, Patrick says he’s always had a choice in drinking, even during initiation.

“Even though people were saying the words ‘you have to drink’ … I knew they weren’t going to crack my mouth open and pour it in my mouth,” he said.

However, he has heard of other students being coerced into drinking in recent years.

“I think definitely there were a few people who get power hungry, and there have been people who have been physically forced to drink,” he acknowledged.

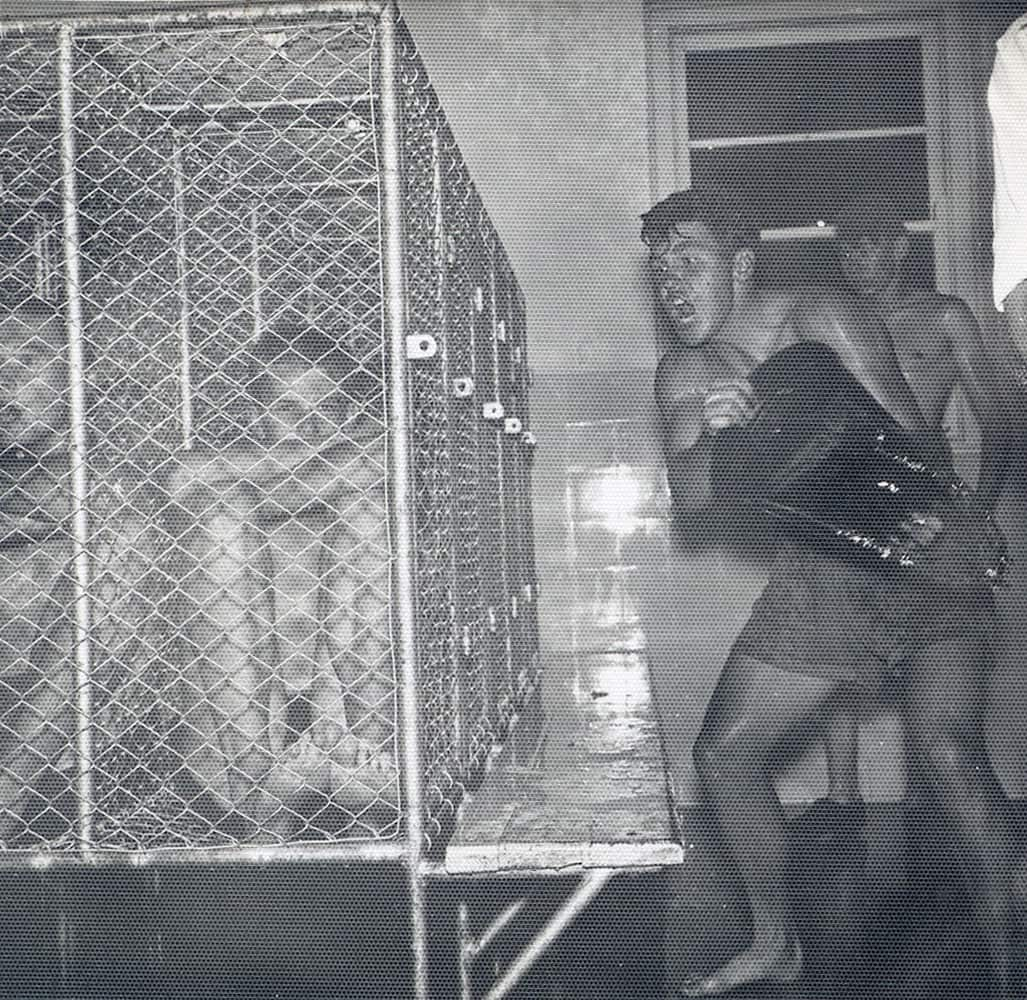

Initiates being put in cages and apparently having liquid thrown on them in 1957. Credit: Western Sydney University Archives Collection: Ref. D16/1470761

Patrick said HAC is now actively trying to change its culture, including getting rid of controversial hazing rituals like the silo climb and molasses army crawl.

“[We’re] not trying to abuse any power or anything, just really focusing on the fun aspects and the teaching aspects instead of the ‘you have to do this’,” Patrick said.

“Most of the people, they don’t want this dirty shit happening — they want people to have fun. And I think the university really gets in our way with that.”

Patrick says Western Sydney University’s zero-tolerance approach to hazing and motting makes students feel conflicted about reporting incidents where they feel unsafe.

He alleges he was groped at a frat party, but didn’t report it to the university, fearing he would be punished for taking part in a HAC event.

“I felt like I couldn’t go to the university… they’re going to say, ‘well, okay, why were you at this party?’,” he said.

“One time we had come home from the bar and one of my mates was missing, and we knew he was drunk, and I wanted to call the residential assistant to check if he’s in his room or not.”

“But I knew that if I did that, I would get suspended.”

To many of the other students on campus, HAC remains a closely-guarded secret.

Niruban Dhanasekaran is the SRC representative for the Hawkesbury campus. Despite studying at the university for almost two years, he hasn’t heard of any HAC events or activities.

“We haven’t [been] contacted from anyone about any issues related to HAC,” he said.

“If they reach out to SRC, definitely we would address whatever concerns, queries, what they face at our campus.”

Brothers and sisters for life

Patrick says when he first arrived at university, he struggled with social anxiety and his mental health.

He worried about not making friends, but through HAC, he met his partner and made plenty of good friends and it’s a big part of why he’s vouching for the group.

“These third-year boys, they looked after me … even when I was having some self-destructive moments,” he said.

“So much of my life would be so different — and in my opinion, for the worse — if I didn’t have these people.”

“Once a mot, always a mot”: former fraternity members remain part of the brotherhood or sisterhood even after they’ve left uni. Credit: Western Sydney University Archives Collection: Ref. D16/1470786

Patrick said the university’s attention meant it’s been difficult to organise HAC events in recent months.

“There was a group of people who’d organise regular parties and regular activities … none of that’s happening anymore,” he said.

“I really see the benefit of the group … it’s just a great shame to see something that’s been going on for 130 years and benefitted so many people’s lives just go to waste.”

Readers seeking crisis support can contact Lifeline on 13 11 14, the Suicide Call Back Service on 1300 659 467 and Kids Helpline on 1800 55 1800 (for young people aged up to 25). More information and support with mental health is available at beyondblue.org.au and on 1300 22 4636.

If you or someone you know is impacted by sexual assault, call 1800RESPECT on 1800 737 732, text 0458 737 732, or visit 1800RESPECT.org.au. In an emergency, call 000.